Introduction

Reinhardt’s virtuosity and prolific body of work with the Quintette du Hot Club de France is held as the pinnacle of Gypsy Jazz. As a result, Reinhardt is portrayed as the innovator and common denominator in the practice of Gypsy Jazz guitar. This first chapter will outline musical elements synonymous with the ‘classical’ (i.e. traditional) style of Gypsy Jazz guitar. The study will mention Reinhardt’s European contemporaries, also held to be innovators of the classical style of Gypsy Jazz. In particular, Pierre Joseph ‘Baro’ Ferret. My findings will demonstrate the technical specifications that define Gypsy Jazz guitar.

The second chapter will discuss guitarists of the 1970s who brought about a crisis in tradition, and a modernisation of the Gypsy Jazz style. This study will demonstrate the music’s correlation with American Jazz of the 1970s, where a similar subservience and reverence to the music occurs. I will include transcriptions and analyses of performances, demonstrating similarities (i.e. conservation) and differences (i.e. innovations) in comparison to the work of the ‘classical’ pioneers such as Django Reinhardt and Baro Ferret. I will reiterate points made in the first chapter concerning the traditional approach to technique, repertoire and instrumentation. I hope to find similarities in both the classical style and modernisation throughout the 1970s (i.e. Jazz Fusion), in order to more accurately define the genre in terms of its musical components, and its processual evolution.

The final chapter will collate my findings concerning the part played by ethnic, cultural and musical characteristics in the evolving genre, and to establish a definition of Gypsy Jazz up to the 1970s. At that time, the art of the authentic ‘Gypsy’ sound was considered to be relayed by a certain circle of performers; in effect a synonym of Reinhardt’s style. However, this is problematic since it creates a deceptive conflation between musical character and ethnicity. Therefore, this classification of the ‘Gypsy’ genre is not merely reductive, but inherently confused. This chapter will focus on the theoretical thinking of Paul Gilroy in ‘The Black Atlantic’ and ideas of Cosmopolitanism within the genre.

Since the 1970s further generations of Gypsy Jazz musicians have based their musical style on fundamental characteristics of Reinhardt’s music, thus conserving a canon of musical characteristics that have defined the music as Gypsy Jazz. However, I will argue that Gypsy Jazz, as with other genres, involves complex and interconnected evolutionary processes concerning repertoire, technique, instrumentation and other musical characteristics across time.

The classical style of Gypsy Jazz

Example 1

Public Domain Image of Django Reinhardt in New York (November 1946)

This is by no means a comprehensive study of Gypsy Jazz technique, but constitutes a list of musical characteristics that are incorporated in both classical and modern Gypsy Jazz. It seems that certain elements of Gypsy Jazz music have been defined solely through technical and performance aspects. These techniques are often exclusive to the genre, and are universally practiced amongst established Gypsy Jazz musicians. Therefore, I will assert that they can be seen as a common denominator as they are still practiced almost exclusively by guitarists of the style, offering strong evidence of conservation within the genre and of Reinhardt’s legacy and personal technique.

The music, which I shall refer to as ‘classical’ Gypsy Jazz, was a radical innovation at the time the Quintette du Hot Club de France was born in 1934. Despite many similarities to American Swing music, it was still considered too ‘Modern’ to be commercially successful. Jeffrey H. Jackson states that the Hot Club musicians, “initially doubted their marketability as a band, and their long efforts to gain a recording contract demonstrated ongoing reluctance on the part of the music industry to accept them.” Even Reinhardt considered the movement towards American Jazz as a modernisation: “By 1926 Django had heard the first rumblings of American jazz in France, when he heard Billy Arnold’s Novelty Jazz Band at the l’Abbaye de Theleme restaurant in Pigalle. To Django, this music was modern, wild and free.”

Rest-Stroke Picking

Example 2

Boulou Ferre pictured using the rest-stroke picking technique on a ‘Grand Bouche’ Selmer replica.

Despite Reinhardt’s disability in his left hand, it was more his right hand technique that became synonymous with the classical Gypsy Jazz technique. The techniques apparent in Reinhardt’s style are considered to be unsurpassed in terms of their suitability to the music. In an interview with (non-Roma) Gypsy Jazz guitarist, Jonny Hepbir said: “Personally, I take all my technical lessons from Django and the Roma. For Gypsy Jazz, they tick all the boxes for me.” Rest-stroke picking has been used throughout the history of the genre, but the technique stemmed from an archaic practice, and although seemingly affiliated with Reinhardt’s own style, was by no means conceived by him.

Rest-stroke picking involves the use of down strokes, immediately anchoring the plectrum on the string directly underneath. This motion is employed with every note, however it has two exceptions. The first exception is when playing the 1st string (top E), which has no neighboring string below it. In this case, the wrist must swing back up, instead of ‘bouncing’ from another. The second is up-strokes, often related to ‘Alternative’ picking. This is employed for faster passages where it is seemingly ‘unnatural’, and often impossible, to down pick every note. However, a new string is always executed with a down-stroke. These exceptions are unavoidable as one of the constraints of the instrument, and work well idiomatically.

This plectrum technique facilitates often-powerful down-strokes on stringed instruments and has been applied to Lute instruments such as the Oud and Bouzouki. In addition it has also played an important role in Italian classical Mandolin. The technique produces a greater volume, audible above other musicians when needed, most obviously whilst soloing. As I have stated, the technique is an archaic practice, but later chapters will further demonstrate its relevance to modern performance.

Relaxation of the wrist is key to rest-stroke picking. The picking hand, levitates above the body of the guitar, so that the palm is not in contact with the bridge or strings. The wrist is usually near to a 45-degree angle with the forearm. The middle, ring and little finger often used to gently anchor the hand to the body of the instrument. This technique is sometimes referred to as ‘broken wrist’, first termed by Biréli Lagrène, due to the inclination of his own wrist. The introduction of electric guitars and amplification did not deter Reinhardt, nor generations after him, from using this technique despite the volume of the acoustic instrument no longer being a constraint. Refer to Track 1 to hear Reinhardt performing on an electric guitar, with rest-stroke picking (Anouman, Django Reinhardt).

The tone produced is heard in Reinhardt’s solo section, from 1:29-2:12 and most noticeable during the diminished phrase at 1:58; notice the fluidity and strong attack. Lagrène states that:

“The secret of this music is not that much the left hand, it’s more the right hand. The pick is very important, too. You have to have those thick picks to have the round sound. When I play that music, my wrist automatically inclines, like a broken wrist. But if I play on an electric guitar, my wrist lays right on the bridge. Because if I do it while playing the Gypsy music, I don’t have enough strength when I play with my wrist on the bridge. It has to be floating, sort of. And this is where the sound comes from. [He plays the same lick with the wrist floating and then resting on the bridge.] With the wrist on the bridge, it doesn’t sound as powerful. It’s a little different approach.”

The technique could be compared to the motion of shaking out a lighted match. Examples 1 and 2 below, illustrate how the picking hand should look. Example 3 demonstrates the wrist fully relaxed after executing a down-stroke across all of the strings. Example 4 demonstrates the inclination of the wrist when returning to a neighboring string above. The middle, ring and little finger are as relaxed as possible, to avoid any tension in the hand.

Example 3

Relaxation of the wrist after down-stroke.

Example 4

Inclination of the wrist, returning to a neighboring string.

The traditional picking technique for American Jazz Guitar involves the hand resting on the bridge, and alternate picking or finger-style picking is habitual. Refer to Track 2 (Cherokee, Angelo Debarre) on the included CD for an example of how rest-stroke picking from a modern Gypsy guitarist sounds in comparison to alternate picking on Track 3 (Cherokee, Joe Pass).

Both pieces are performed on acoustic instruments.

Traditional American style alternate-picking (Track 3), although arguably as dynamic in certain situations such as on an electric guitar, is less focused on dynamic force for louder acoustic performances. As mentioned earlier, rest-stroke picking was initially intended for acoustic instruments. Such a potentially powerful technique is not required when amplification easily resolves problems regarding balance and projection in an ensemble. However rest-stroke picking is still used in classical Gypsy Jazz, regardless of what instrument is being played, whether acoustic or electric. Alternate-picking gives a more balanced level between attack and decay, mainly due to less ‘plectrum-noise’ – the sound made when the plectrum comes in contact with the string.

Plectrum

The type of plectrum used in Gypsy Jazz is very important in itself; it is traditionally very thick, ranging from around 2.5mm to 5mm. A Gypsy Jazz plectrum delivers a softer attack, due to a smoother, and rounder, resistance in contact with a string. However, a greater volume is produced as a result of the plectrum’s weight. The sound of the thicker plectrum combined with rest-stroke picking delivers a tone with very strong attack and fast decay depending on the set-up and specifications of the guitar. The plectrum and it’s relation to rest-stroke picking is a vital feature of the classical style, my second chapter will demonstrate that this remained a constant during the process of modernisation of the 1970s.

Instrumentation

Example 5

The Quintette du Hot Club de France. Reinhardt and Baro Ferret both using Selmer ‘Grand Bouche’ instruments.

The majority of Gypsy Jazz guitarists use instruments based on the designs by Mario Maccaferri for the Selmer instrument company of Paris (1930-33). They are categorised into two different styles: ‘Grand Bouche’ (large mouth) and ‘Petit Bouche’ (small mouth). These guitars, primarily replicas, are still used almost exclusively for the style and have remained a constant throughout the 1970s until the present day. All one has to do is look at the promotional poster for the 2013 ‘Samois sur Seine’ (Django Reinhardt) festival which portrays a Selmer Macaferri style guitar in silhouette, complete with a ‘moustache’ bridge piece – a feature of the instrument which has become associated with the personality of Reinhardt himself (Example 6). This evidences the way in which the personality ‘cult’ of Reinhardt is significant in the popularity and tradition of the genre; an element that is not directly involved with aspects of the music itself. Indeed, there is a Selmer hybrid brand of ‘Moustache Guitars’ named after Reinhardt’s ‘trademark’ moustache.

Example 6

Festival Django Reinhardt 2013 poster with ‘Moustache’ Bridge piece.

The Quintette du Hot Club de France set the example of how it was considered that a Gypsy Jazz quintet should be orchestrated. This involved a double bass (Louis Vola) and two rhythm guitars (Joseph Reinhardt, Roger Chaput and Baro Ferret) as the foundation for rhythm accompaniment. In addition there were two soloists on violin and guitar, namely Stéphane Grappelli and Django Reinhardt. Grappelli performed with the quintet until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1940, and was later replaced by clarinetist and tenor saxophonist, Hubert Rostaing. In 1946, Reinhardt toured in England and Switzerland (a reunion with Grappelli), and joined Duke Ellington’s band in America as a soloist. Grappelli would later return to the quintet in 1947, occasionally performing with Reinhardt.

La Pompe

This fundamental picking technique crosses the barrier between rhythm and lead performance but they both share the same inclination of the wrist. This rhythm technique is called La Pompe (‘The Pump’) and constitutes a fundamental characteristic of the music. Dregni describes La Pompe as being, “The fierce boom-chick, boom-chick rhythm that would become the trademark of Gypsy jazz”. According to my interviews with both Jonny Hepbir and Denis Chang, a respect and understanding of Reinhardt’s music is vital to perform the music appropriately. La Pompe is a strong indication of conservation within the style; it is almost always used, with a few exceptions, which I will discuss later. Jackson writes:

“Despite the confusion [of genre] during these early days, there was at least one common musical meaning when people in France invoked the term jazz: it meant rhythm and the instruments used to make it. Above all, the drums—la batterie—were not only the most prominent instrument but their mere presence, many believed, made any band into a jazz band.”

La Pompe is apparent in Reinhardt’s first recording with the Quintette du Hot Club de France. Listen to Track 4 to hear Reinhardt’s version of ‘Dinah’.

In this version we hear the vital La Pompe throughout its entirety, further embellished during Grappelli’s solo at 1:13-1:35, with Reinhardt joining the rhythm section and playing swung quaver rhythms over straight crotchet rhythms supplied by Joseph Reinhardt and Roger Chaput. Reinhardt is often heard supplementing the rhythm section whilst other instrumentalists are taking a solo. Reinhardt provides a rhythm similar to ‘shuffle’, associated with American Big Bands of the 1930s. This style of rhythm can be heard on ‘Mushmouth Shuffle’ (Track 5), recorded in 1930 by Jelly Roll Morton & The Red Hot Peppers.

The shuffle rhythm is most noticeable on the hi-hat from 0:11 onwards as a rhythmical foundation. Similarly to this, the rhythmic features of La Pompe are extremely similar to Swing Band associated rhythmic styles such as ‘Stomp’. When referring to ‘Kansas City Stomps’, also by Jelly Roll Morton (Track 6), you can hear the blatant rhythmic similarities to La Pompe in ‘Dinah’ (Reinhardt).

I shall assert that the only dramatic musical differentiation to American Swing Jazz rhythm is instrumentation and consequently idioms of the guitar itself: techniques such as La Pompe, and of course, the absence of drums.

Nolan believes that this rhythmic pattern (La Pompe) is an example of conservation in the style: “The rhythm is the other defining technique which absolutely defines this music. It replaces the drums and gives it that recognisable swing not seen in other music.” Dregni states that La Pompe was a way of creating “a full band’s sound with a minimum of instrumentation.” Both Nolan and Dregni have stated it is not the importance of the rhythm (i.e straight crotchets) itself that defines the music as Gypsy Jazz, but the rhythmic instrumentation. This is what separates Gypsy Jazz from Swing Band Jazz. Moon writes: “There was no drummer, and this gave the group an agile, reeling, free-spirited sound.” Therefore, this choice of instrumentation is a key element of the classical style that has remained a constant throughout the modernisation of the 1970s.

For Gypsy Waltzes, a similar technique to La Pompe is applied. A chord is played every beat of the bar (in 3 / 4 time signature) with accents often placed on beats 2 and 3. Otherwise it is common to play this rhythm ‘straight’ without accents. Also, there is very often a ‘fill’ on the second division of beat 3, leading into the beginning of every bar. This embellishment is used sparingly, not to distract from solo performers. Gypsy Waltzes stem from French Musette, and although it is not strictly ‘La Pompe’, it is extremely common in classical Gypsy Jazz music offering further evidence that the Gypsy Jazz genre has evolved from diverse influences. According to Alain Antonietto, Baro Ferret was: “the brilliant soloist in groups that all bear his stamp: the swing musettes”. Musette was also a combination of musical traditions, including the laments of the Auvergnat bagpipe and Italian accordion melodies.

For an example of the very straightforward approach to Gypsy (swing) Waltz rhythm, refer to Track 7 which is Baro Ferret’s composition, ‘Panique’ – a recording from 1949.

Baro Ferret was perhaps more known for his waltz compositions than Reinhardt, and he released an album of Gypsy Waltzes, entitled ‘Swing Valses’ in 1965/6 (re-released in 1988 on Hot Club Records). Although a practitioner of classical Gypsy Jazz, Baro Ferret became more influenced by modern American jazz when ‘Swing Valses’ was released. I will talk more about this in the following chapter. Ferret’s ‘Panique’ is predominantly a traditional Gypsy Waltz, but with some strong Swing influences. This can be heard from 0:31-0:35 with emphasis on syncopated rhythms, not dissimilar to rhythmic arrangements of American Swing Bands. Within this particular recording, beats 2 and 3 are near identical to 1, without noticeable accents in a similar way to traditional La Pompe, spreading dynamics evenly across every beat.

Form

As far as musical form is concerned, classical Gypsy Jazz is structured; in it’s most basic form, ABA. This is with the exception of through-composed pieces. What I mean by this is the classical Gypsy Jazz repertoire often demonstrates a ‘head’ section (A), followed by instrumental solo/s (B), ending with a recapitulation to the opening ‘head’ section (A). This also demonstrates similarities to American Swing Jazz. In Reinhardt’s version of Dinah (1934) (Track 4), the structure follows much the same pattern. The song is introduced with a 4 bar turnaround supplied by Reinhardt. The head section then follows, which consists of a A,A,B,A structure, whereby each A/B lasts 8 bars. Therefore the overall length of the melody or head section, played by Reinhardt, is 32 bars. This adheres to Adorno’s theory of standardization of chorus structure in popular music, further demonstrating it’s relation to the popular genre of American Jazz. This 32 bar structure is then repeated throughout, as a basis for instrumental improvisation. The first solo section can be heard from 0:40- 1:14, played by Reinhardt. The second instrumental solo, from 1:14-1:51, is taken by Grappelli. The final instrumental solo predominantly focuses on Grappelli, with embellishments and a call-and-response style melodic interest supplied by Reinhardt (1:51-2:24). Although the head section does not return in its entirety, the songs abrupt ending echoes the turnaround from the last A section of the melody.

This structure, by comparison to one of Reinhardt’s American contemporaries, Charlie Christian, follows much the same pattern. Although recorded later, specifically in 1939, Christian’s more ‘American’ approach to instrumentation and perhaps soloing do not distract from its very similar approach to structure and form. In this particular recording (Track 8), there is also a 4 bar introduction leading into the head section, this time played by vibraphone.

The head section or chorus is also 32 bars in length, and instrumental solos last for the same duration, over the same harmonic structure. The first solo, performed on vibraphone starts from 0:39. Christian takes the next chorus from 1:14. The next instrumental solo is taken by Benny Goodman on clarinet from 1:49, interrupted by a vibraphone solo in the B section, and returning to clarinet on the final A. The final solo section echoes that of Reinhardt and Grappelli’s recording, whereby, Goodman and Lionel Hampton (vibraphone) exchange melodic ideas in a call-and-response style. This can be heard from 2:24. Similarly to the version recorded by Reinhardt, the song ends abruptly with a final turnaround of the A section.

Musical Examples and Devices

This section will discuss certain idioms and consequently devices associated with the guitar. For example, subtleties such as vibrato can be used differently depending on the style/tempi of the tune being performed. More vibratos are employed when playing a ballad (Such as Reinhardt’s composition Nuages), and less for faster tunes especially in Reinhardt’s version of Les Yeux Noirs (1947). Similarly, this recording of Les Yeux Noirs (Track 9)demonstrates Reinhardt’s innovative, and extensively used tremolo technique achieved by fast strumming of chords with the picking hand, and normally deployed on the top 3 or 4 strings.

This technique is also similar to shaking out a lighted match, but considerably faster. It gives the impression of a timbre similar to a “string or brass section, especially when certain notes are sharpened or flattened or where extra notes are added, creating movements within the chord.” Again, this relation to brass sections is an acknowledgement of Swing Band movements in America. This can be heard in Reinhardt’s recording of Les Yeux Noirs, Track 9 from 1:50 to 1:58.

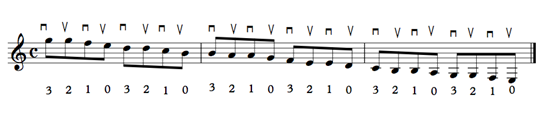

A relatively common trait of this style involves devices used to connect and approach melodic phrases. One of these devices is a semi-chromatic run designed to be played very fast (usually quavers/semiquavers depending on the tempo of the song). This run is performed starting on an open string, followed by fretting the 1st, 2nd and 3rd frets consecutively. This is then repeated on the string below, until the desired note is reached. It is important to note that doing this is not strictly a chromatic scale because in order for it to work more efficiently, it is necessary to miss certain notes of the chromatic scale. This method is much easier to use than a purely chromatic run, which requires a more cumbersome picking pattern at fast tempi. The following (Example 7) is a notated example, with an indication for down/up picking and fingerings.

Example 7

Descending semi-chromatic scale as used in Minor Swing (Reinhardt).

This devise involves strict alternative picking combined with rest-stroke technique. This semi-chromatic scale can be heard as a descending connective phrase in Reinhardt’s ‘Minor Swing’ 1937 (Track 10) at 1:20.

This device is designed to work idiomatically for the instrument, hence it’s association and distinct relation to Gypsy Jazz guitar and not other styles and instruments. There are exceptions for this, where a full chromatic scale is used, usually when the range of the phrase is less than an octave. This can be heard in Reinhardt’s recording of ‘When Day Is Done’ (1937) at 0:47 on Track. 11.

Nuages

Nuages is one of Reinhardt’s most celebrated compositions, which has now become of key importance within the Gypsy Jazz repertoire (Track 12).

This composition in particular demonstrates minor II-V-I turnaround, which again adds subtle changes to the harmony and creates the illusion of static chord movements. This can be heard from the transition of chord II (A-7b5) to chord V (D7b9), where the only movement between chords is G, the seventh of A-7b5 to F#, the 3rd of D7b9. This minor II-V progression naturally leads into G minor, however Reinhardt prefers in this case to lead into the tonic major. Also within the harmonic progression, the root notes between Eb9, and A-7b5 present an interval of a tritone. Similarly, the chromaticism in the melody is followed by parallel (semitone) chord movements within the harmonic progression: A7-Ab7-A7 (0:40-0:44).

Ettiene ‘Patotte’ Bosquet

Many guitarists have copied Reinhardt’s improvisations to popular recordings, and have continued to perform them throughout history. A famous example of this dedication can be heard in Ettiene ‘Patotte’ Bosquet’s recording of Les Yeux Noirs (Dark Eyes) on Track 13.

This recording starts with Bosquet’s own arrangement of Les Yeux Noirs head section, leading into a note-for-note copy of Reinhardt’s own improvisation such as in Track 9. Both recordings are played on electric guitar, and demonstrate Bosquet’s loyalty to Reinhardt. This recording was produced at some point in the 1950s, although I am unable to find an exact date for this performance. Bosquet’s own improvisation starts from 0:58 on Track 13, and continues in a similar vein but, according to John Etheridge, arguably without the driving force, speed and technical precision executed by Reinhardt’s improvisation. Clearly, Reinhardt is still considered to be the ‘bench-mark’ by which other guitarists are judged. This demonstrates that around the 50s, there was still a focus on purely replicating the style of Reinhardt, to the point of reproducing Reinhardt’s own improvisations entirely. It also shows that Reinhardt’s work was still considered important even during the beginning of the styles reinvention. In the next chapter, I shall discuss the reinvention of style inflected by American influences of the time.

Example 8

Django Reinhardt with Duke Ellington. November 1946.

Gypsy Jazz in the 1970s

Crisis in Tradition

“On the notion of modernity. It is a vexed question. Is not every era ‘modern’ in relation to the preceding one? It seems that at least one of the components of ‘our’ modernity is the spread of the awareness we have of it. The awareness of our awareness (the double, the second degree) is our source of strength and or torment.”

Edouard Glissant.

In an interview that I undertook with Robin Nolan, he stated the importance of remaining open to modernisation and invention, and argued that Reinhardt himself was keen on this ideology:

“Tradition is a great place to start but you must always remember that Django was an innovator and was constantly looking for new ideas and music. He was ahead of his time. I’m not so into preserving the tradition but many are.”

This crisis in tradition is a common reoccurrence seemingly throughout the history of Gypsy Jazz, even with classical pioneers such as Baro Ferret. In the words of Antonietto, his swing musettes were, “long scorned by purists. Together with Gus Viseur and Jo Privat he explored the swing waltz, a new and rather controversial concept: how could a waltz (3/4) swing (4/4)?” This quotation further proves that these crises in tradition are evident throughout the history of the music, and the 1970s were no exception.

The 1970s presented new ways of thinking about Jazz music, and this undoubtedly effected the way in which Gypsy Jazz was performed around the same time. However, this is not to say that there were not traditionalists. Many Gypsy Jazz musicians at least thought they remained faithful to the classical style, although this interpretation of faithfulness was often interpreted in different ways. However I will argue that this definition of ‘traditional’ is an evolutionary process, much like the music itself. According to Yurochko:

“The ‘60s represented one of the most diverse periods of jazz history, with several styles carried over from the ‘50s, those developed during the ‘60s, and new influences that would become an important part of the ‘70s. Early European classical music influenced an important style in the ‘50s that developed into third stream music and free jazz … This music provided little harmonic base, in an attempt to free melody and rhythm with improvisational spontaneity.”

This freer approach to the music is apparent in many Gypsy Jazz recordings around the 1970s when Free Jazz, as stated by Wilson, was considered to be `the new style’ while, as he states: “traditionalists stuck to previous styles from the ‘50s.” Indeed, Wilson argues that “The History of jazz from the time of it’s emergence from the blues (and elsewhere) through at least until the sixties is, on the contrary, a history of expanding freedom, as the music progressively distances itself from standardized musical forms in a series of shocks and ruptures.” This closely links to what Paul Gilroy defines as the complex “contingent loops and fractal trajectories” involved in the evolution of black music that I will discuss in depth in my third chapter.

American Jazz music of the 1970s was seemingly influenced by Rock music of the time, and Miles Davis’ ‘Bitches Brew’, released in 1970, is considered to be the first commercially successful Jazz Fusion recording. ‘The Penguin Guide to Jazz’ stated that Bitches Brew was, “one of the most remarkable creative statements of the last half-century, in any artistic form. It is also profoundly flawed, a gigantic torso of burstingly noisy music that absolutely refuses to resolve itself under any recognized guise.” The recording was also extremely commercially successful, which led on to Miles Davis performing at ‘Rock’ music festivals such as the Isle of White Festival (29/08/1970).

According to the ‘Oxford Companion to Music’, Jazz Fusion was:

“A style from the late 1960s and early 70s that combined modern jazz techniques with the then current style of soul and rock; it thus brought jazz for a time nearer to the commercial tastes of the day, including the use of electronic instruments.”

However, Gypsy Jazz remained seemingly uninfluenced by Rock inflections until artists such as Boulou and Elios Ferre followed Jazz Fusion conventions and studio techniques to enhance their music (although only Boulou Ferre in the 1970s). Other than this there is little evidence to suggest that Gypsy Jazz instantaneously correlated with the Jazz Fusion movement. This is not to say that other traditional (early 20th century) guitar styles remained autonomous of this movement. In fact, Paco de Lucia (1947-2014), the well-known Flamenco guitarist, was drawn into the Jazz Fusion movement, and featured on Al Di Meola’s album, ‘Elegant Gypsy’ (1977). Paco de Lucia’s influence on Jazz Fusion also spawned a new genre: ‘New Flamenco. ‘ This demonstrates the further global amalgamation of commercial Rock music of the 1970s as a primed canvas from which musicians took their influence. I will consider a range of musical examples to demonstrate the correlation between Gypsy Jazz and Jazz Fusion/ Free Jazz in the 70s and 80s.

Musical Examples

Plectrum technique, rhythm and repertoire alone constitute evidence of conservation in Gypsy Jazz guitar style. However, the fact of Reinhardt’s quasi deification in the genre, and that he standardised this style of performance on the guitar, is the reason why it is still apparent in modern performers. Denis Chang states that there is:

“Nothing wrong with the modern scene, but people should dig much, much deeper [the roots of the music should not be ignored] if they are really passionate about this style. In fact, the pioneers of the modern style have done just that, Adrien Moignard comes to mind; that is what sets them apart from the other modern players who have ignored the roots of the style. My opinion of course!”

Chang’s assertion that one must explore ‘deeper’ into the roots of the music could be considered a partial view of what might constitute the roots of Gypsy Jazz since his stance suggests that this genre was spawned by Reinhardt himself. Clearly its origins go back much further, and whilst I believe that Chang was acknowledging the importance of the history of the genre pre-dating Reinhardt, it is arguable that too much concentration on the past is an overly reverent and conservative view point, especially considering that modernisation was at the heart of the inception of the Quintette du Hot Club de France. I will now look into particular recordings of the 1970s, demonstrating this crisis of tradition.

Babik Reinhardt

Ironically, Django Reinhardt’s son, Babik Reinhardt was also known to have shown a strong interest in Jazz Fusion. Although he never recorded commercially until the late 1980s there is video evidence of Babik experimenting with a MIDI guitar and electronic backing tracks. Furthermore, Babik Reinhardt released a Jazz Fusion album entitled, ‘Live’ (1989), where he was largely accompanied by programmed backing tracks arranged by Reinhardt himself. The move towards electronic instruments undoubtedly raised questions of authenticity, not only in Gypsy Jazz music but other jazz genres. This development of music technology proves to be a key factor for these crises in tradition throughout history. The fact that ‘classical’ instrumentation, as mentioned earlier, is a defining factor of Gypsy Jazz music, it is difficult to define such evolutionary style and technology as following the original concepts of the genre. According to Pinch and Bijsterveld in ‘Should One Applaud?’:

“The impact of technology upon music is not solely a twentieth-century phenomenon. Throughout history, new instruments and instrument components drawing upon technical possibilities of the day have often incited debates as to their legitimacy and place within musical culture. The arrival of the pianoforte into a culture that revered the harpsichord was for some an unwarranted intrusion by a mechanical device.”

What Pinch and Bijsterveld argue here is that newer technologies will always bring about a crisis in tradition and even if at first seemingly controversial, it is perhaps an element of the evolutionary nature of music. The inevitability of technological advancement may present a crisis in genre, but it could be argued that Babik Reinhardt’s close relation to Django Reinhardt is reason enough to assume its validity within the genre. Despite this, Babik was also a performer of the ‘classical’ style, in many cases as a way of paying homage to his father. This can be heard on the album, ‘New Quintette du Hot Club de France’, (1999). Although Babik Reinhardt was not recording music commercially during the 1970s, it is clear from these examples where his influence came from and evidences an acceptance of technological advancements as a way of ‘enhancing’ his music.

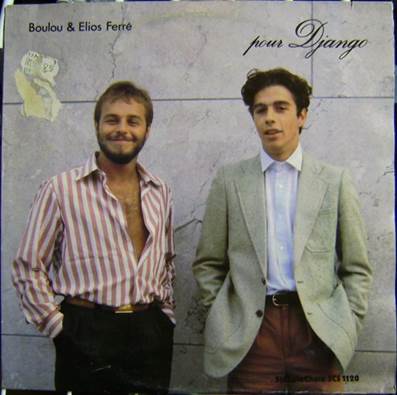

Boulou and Elios Ferre

Example 9

The Album cover for Boulou & Elios Ferre’s ‘Pour Django’.

Within the sleeve notes for ‘Gypsy Jazz’, “His sons [Matelot Ferre] Boulou and Elios carried their father’s music into the future in a fitting contemporary style.” It is arguable that if the music hadn’t moved into a more contemporary style, Gypsy Jazz would have remained a historic performance practice, rather than a living genre.

It is possible that Boulou and Elios Ferre were the main exponents of the ‘modern’ style of Gypsy Jazz. Despite their often-radical negligence towards certain classical features mentioned within the first chapter, they are still firmly bracketed under the Gypsy Jazz label. Whether this is due to their inherent relation to Baro Ferret and Gypsy ethnicity, or musical character is debatable. Here I shall outline features of musical examples of the 1970s and 1980s: whereby Boulou and Elios Ferre arguably step back to more classically inspired works.

Boulou Ferre (Nephew of Joseph ‘Baro’ Ferret), a famed Gypsy Jazz guitarist in his own right, followed the direction of Free Jazz, on an album entitled ‘Homage to Peace’ (1973), alongside the band, ‘Emergency’. The musicality itself is far from Swing-influenced, Gypsy Jazz music presented by Reinhardt. There is no noticeable homage to Reinhardt’s work within these recordings. I am even unsure as to whether traditional rest-stroke picking was used, as the guitars tone is often effected and characteristic of American Jazz Fusion guitarists. Much like Davis’ ‘Bitches Brew’, Boulou Ferre demonstrates many stylistic traits of Rock music of the 1970s, such as distorted guitars and Wah-Wah filtering effects. This can be heard on ‘Infidels’ (Track 14) from 6:52- 7:03 on the album ‘Homage to Peace’.

This use of Wah-Wah can be heard on every track of the album minus ‘Kako Tune’, and it’s association to Rock music, (i.e Jimi Hendrix’s, ‘Electric Lady Land’ 1968) further grounds the assumption that Boulou Ferre was not trying to sound like a Gypsy Jazz guitarist. On a similar note, Boulou Ferre deliberately employs a distorted guitar tone. This can be heard from 2:42- 3:05, also on ‘Infidels’ (Track 14). Ironically, this distorted guitar tone, although not quite as explicit, can be heard in much of Django Reinhardt’s electric guitar work, including Les Yeux Noirs (Track 9). Although this was not specifically intentional, the distortion that can be heard here was the nature of pushing a valve-powered amplifier to a high volume, resulting in a lack of tonal clarity. This distortion can be heard throughout, but most noticeably from 1:28-1:39 why Reinhardt forcefully plays in octaves. It can also be heard when forceful chords with tremolo are deployed from 1:50-1:58. Therefore, although this guitar tone is at first very different to Reinhardt’s own, it is not dissimilar to the tone of Reinhardt’s later work with electric guitar.

The introduction of the Long Play record by Columbia (1948) was another key factor for musical reinvention. By the 1960s, the LP would sell out both 78s and 45s and hold 80% of the market share in comparison to other formats. The fact that musicians in the 1970s were presented with the ability to record more music per side of disc was detrimental to music production of the time. The introduction of the LP was undoubtedly an enabling factor to the modernization of Rock and Jazz Fusion. On Boulu Ferre’s album with the band ‘Emergence’, individual tracks last far more than classical Gypsy Jazz recordings. The opening track, ‘Emergence Theme’, lasts for 15:22. This was a feature of much Jazz Fusion music of the time, similarly to Miles Davis’ ‘Bitches Brew’, with its title track, ‘Bitches Brew’, lasting 27:00.

The harmony within the recordings by the band ‘Emergence’ function extremely modally, leaving an unrestrained approach to improvisation, which shares similarities to the nature of Free Jazz. With this particular example, there is hardly any noticeable evidence of Reinhardt’s musical influence. However, I would argue that the music in this case is not trying to be, or fit into the label of Gypsy Jazz. Indeed, the band name itself suggests an evolution or transformative process moving away from previous incarnations. It is explicitly a Jazz Fusion recording, incorporating instrumentation used in Rock music of the 1970s. This evidence suggests that the only defining feature of Gypsy Jazz is the performer, Boulou Ferre, himself. This is much the same way in which Babik Reinhardt takes a musical step away from the Classical Gypsy Jazz style. In which case, it is not musical style, but ethnicity and relation to the classical masters that places them firmly within the Gypsy Jazz label. I shall talk more in depth about this conflicting debate between musical style and ethnicity in my third chapter.

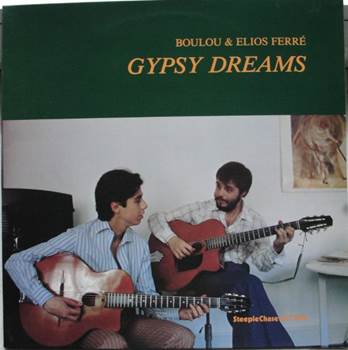

A modern example of ‘Panique’, recorded by Boulou and Elios Ferre can be heard on Track 15 (Nephews of Joseph ‘Baro’ Ferret).

The recording is taken from the album ‘Gypsy Dreams’ (1980). It seems that their version of the piece utilizes a softer rhythm, with an often less abrasive timbre (with grace-notes) at 0:35. This performance is more representative of Modern Jazz than of a Gypsy Waltz, and is characterized by a freer interpretation of classical Gypsy Waltz rhythm, heard at 0:18-0:34. This is one of the rare cases where the rhythm guitar begins by arpeggiating the chords as opposed to playing La Pompe. The opening head section is almost entirely performed this way, resulting in a very modernistic take on the original composition. Their arrangement draws attention to accents in the music with more dynamic contrast creating a modernistic approach to this performance (1:40-1:46). These more aggressive statements give a fresh interpretation to the music that was previously written with more leniencies in tempo, and a generally more free and novel approach to lead performance. This style echoes the concept of this album, namely, as the album title suggests, a surreal or dream-like impression of classical Gypsy Jazz. Although a more recent recording from Boulou Ferre, this is deliberately a conscious move back to the style of Reinhardt. This recording and album, although sharing musical similarities to the modern American Jazz music of the time, is perhaps a step back to a more classically inspired work. I would argue this is due to a returning focus on the acoustic guitar as key instrumentation. Consequently, the idioms of Gypsy Jazz guitar, such as rest-stroke picking, and musical devices (i.e. embellishments such as semi-chromaticism and mordents) are apparent again. Whereas these classical Gypsy Jazz guitar idioms were not in Boulou Ferre’s work with the band ‘Emergence’.

This reinvention is typical of Boulou and Elios’ style, and other example of their modernistic interpretations can be heard on the album ‘Pour Django’ (dedicated to Reinhardt) from 1979. This implies that their stance is one that acknowledges Reinhardt’s legacy, not only in terms of what he left behind, but also in the way that he sought innovation too. I feel that one recording/arrangement in particular encapsulates their modernistic impression on Gypsy Jazz: Rhythm Futur (Track 16), based upon an ominous tritone chord pattern.

This recording also uses studio effects to enhance the music, with added reverb at 1:41, creating an illusory ‘unnatural’ environment and thereby adding to the ‘impossible’ nature of the lead guitar sound. This is unusual for classical Gypsy Jazz recordings, which are generally left untouched by studio effects. These studio enhancements are generally uncommon, and debatably a radical movement away from the musical style of Reinhardt in that they constitute an attempt to embrace the American Fusion movement using electronics as instruments. Despite this, the sleeve notes in their entirety say: “There Is No Overdub On This Record”. The possibility to overdub tracks in the recording is yet another process that opens the debate regarding what may be considered as the authenticity of music production and, as termed by Croft, the ‘liveness’ of the music. Boulou and Elios Ferre have therefore explicitly stated that this album was recorded as a live performance, even though there are certain elements of studio enhancement.

The tempo varies with a gradual accelerando building from 0:25 to 0:51. This is unique to Boulou and Elios’ version and does not occur in Reinhardt’s original composition. Certain motifs are elongated and repeated, and the elements of aggression and bold statements stay true to Boulou and Elios’ own style (such as in Track 16). Rhytm Futur was originally composed by Reinhardt, and was originally through-composed, intentionally not leaving space for improvised instrumental solos. Whereas, in this recording by Boulou and Elios Ferre, there are lengthy instrumental solos, a common stylistic trait of much of the ‘classical’ repertoire, but not Reinhardt’s original intention for his composition. The harmonic progressions remain consistent to Reinhardt’s original composition (Track 17), whereby the opening section is based around an F#7b5b13 chord, played with an emphasis on the tritone between F# and C.

Boulou and Elios Ferre’s modern version also shares the parallel chromaticism within the harmony between G7 and Ab7 as in Reinhardt’s original; this can be heard from 1:21-1:27. With this particular recording, Reinhardt’s original harmonic structure has not been greatly altered, however the solo improvisations are arguably more connected with the ‘Free Jazz’ movements in America surrounding the 1970s and 1980s.

Refer to Nuages (Track 12) to hear this example of Reinhardt’s composition. The generation of ‘Modern’ Gypsy Jazz guitarists following the 1970’s kept many classical aspects of the music, but undoubtedly progressed the style. Refer to Track 18 to hear Boulou and Elios Ferre’s take on this Gypsy Jazz standard from 1985.

The head or melody is still recognisable, despite an ambiguity of harmony and a reluctance to resolve phrases, making it an extremely ‘modern’ take on the standard. Their music was arguably an innovation from certain classical aspects of the music, including an entire negligence of the standardised La Pompe throughout the recording. However, it was not unusual for this to occur in Reinhardt’s solo performances without the Quintette du Hot Club de France, where Reinhardt would perform unaccompanied, with lenient tempi and freer improvisations away from the ‘swing’ style. One can hear Boulou and Elios Ferre’s influence in many of Reinhart’s solo works, although a much clearer tonal centre is apparent. An example of Reinhardt’s freer compositions is evident in ‘Improvisation’. This can be heard on Track 19.

Example 10

Album cover for ‘Gypsy Dreams’. Boulou and Elios both pictured using Selmer ‘petit bouche’ replica guitars.

Despite the more obvious connections with classical Gypsy Jazz, there are certain fundamental elements that are comparable to Jazz Fusion, returning to what Richard Cook wrote about music, ‘that absolutely refuses to resolve itself under any recognized guise’.

Repertoire

Although he has seemingly been canonized, Reinhardt’s technique and melodic style is not the only constant amongst Gypsy Jazz guitarists and performers; the repertoire of the Gypsy Jazz genre is also extremely important. The repertoire that is considered exclusively Gypsy Jazz are those that were composed by either Reinhardt and/or Grappelli in the Quintette du Hot Club de France. According to James Michael, “He was a gifted composer of short evocative pieces and had a flair for pacing a performance so that the maximum variety could be wrung from it without compromising its homogeneity.”

Despite much of the Gypsy Jazz repertoire originating from American Swing music, Gypsy Jazz focuses predominantly on the guitar. Whereas American Swing music utilizes guitar as a predominantly rhythm based instrument, (this of course has exceptions as mentioned earlier), Gypsy Jazz has predominantly string based arrangements. Regardless of musical developments and supposed reinvention within the genre, instrumentation, in particular the guitar and it’s idioms, remain fundamental to the style. This is, of course, nothing new when we look back to the origins of the music initiated by Reinhardt and the Quintette du Hot Club de France, as music is continuously evolving through the interaction with external influences.

One very recent recording could be described a prime example of this musical evolution: La Fuente ft. The Rosenberg Trio, ‘Guitarra’ (2010). In this recording, DJ La Fuente collaborates with the Rosenberg Trio to create an electronic dance piece with Gypsy Jazz influences. This example (Track 20), shares rhythmic emphasis on every beat, (this is the only similarity to La Pompe) although this electronic ‘four-on-the-floor’ is far more characteristic of electronic dance music, due to its choice of instrumentation (i.e. electronic drum kit).

The involvement of Nonnie Rosenberg (bass guitar and double bass) is seemingly to supply a bass line in intervals of a 5th, to outline the base harmony. This can be heard most clearly from 0:32-0:46, although the harmony remains static throughout. The rhythm guitar, played by Nous’che Rosenberg, accents on the offbeat and performs embellishments similar to flamenco style rasgueado (hence the Spanish title, ‘Guitarra’) from 1:30-1:39, but this is seemingly his only role within the track. Stochelo Rosenberg (solo guitar) performs lengthy cadenzas throughout the piece 0:20-0:31 where Nous’che supplies arpeggiated chordal accompaniment, and frequently returns to the main riff at 1:24-1:38. Therefore, there is nothing obviously in common musically with the classical style of Gypsy Jazz other than the inclusion of a Gypsy Jazz trio (i.e. some elements of instrumentation). However, what this effectively demonstrates is the widespread influence of Gypsy Jazz beyond that associated directly with American Jazz music. This proves to be the case in the 1970s also, where Rock music could be considered as just as much of an influence on Gypsy Jazz musicians (i.e. Boulou Ferre) than solely American Jazz of the time.

Many modern guitarists are arguably performers of a pre-ordained style, following stylistic boundaries that are already, in a sense, historical. This classification of genre does not allow for a ‘living’ and evolutionary process involving continual external influences, but remains tethered to a certain point in history. The innovators of the genre, such as Boulou and Elios Ferre, believe that they effectively preserve some essence of Gypsy Jazz, even though the style becomes ever more influenced by American Jazz. This links back to Paul Gilroy’s assertion of Jazz as a ‘processual’ and evolutionary music; something that Gilroy would argue is evident in all creative processes.

Cosmopolitanism and Gypsy Jazz

Paul Gilroy describes the nature of artistic expression and creation as ‘processual;’ this is essentially what makes the music a living genre as opposed to a historical practice. In ‘Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers (Issues of Our Time),’ (2006) Kwame Anthony Appiah argues that cultural borders become highly problematic once they become too entrenched with notions of nationalism and that it is essential that the notion of “citizens of the world” be developed. A consideration of the theory of Cosmopolitanism would therefore identify that the genre of Gypsy Jazz, defined as a continuance and devotion to it’s prescribed classical features and ‘rules,’ is somewhat deadening. Thus, Gilroy and Appiah highlight the way in which cultural identity is a mutable and continuing process. Similarly, in ‘Metamorphoses,’ Rosi Braidotti argues against the notion of linear progression stating that: “In spite of the sustained efforts of many radical critics, the mental habits of linearity and objectivity persist in their hegemonic hold over our thinking. Thus, it is by far simpler to think about the concept A or B, or of B as non-A, rather than the process of what goes on in between A and B… They tend to become frozen in spatial, metaphorical modes of representation which itemize them as ‘problems’.” Therefore, static categorizations of genre are hierarchically structured and negatively arrived at in terms of simple binary oppositions. What Braidotti states as ‘the process of what goes on in between A and B’ is much more complex involving what Gilroy identifies as ‘contingent loops’ and ‘fractal trajectories.’ Arguably, this continuing evolution in the case of Gypsy Jazz, has taken Reinhardt’s legacy in different directions.

Gilroy, Appiah and Braidotti essentially hold the same opinion that genre is not ‘set in stone.’ Gilroy’s writing in The Black Atlantic discusses the globalization of black music, and questions the importance of authenticity in regard to global manifestations of the same cultural forms; Gypsy Jazz initially had its roots in black music as well as in Roma traditions. In this case, it can be argued that Gypsy Jazz, and indeed all genres of music, are what Braidotti describes as a ‘hybrid’ mix. Braidotti writes that one cannot live in the 21st century if one cannot accept change: “We live in permanent processes of transition, hybridization and nomadization, and these in-between states and stages defy the established modes of theoretical representation.” It is the need to accept evolution and transformation that defines postmodern existence.

Leitch agrees that there are substantial questions regarding the direction of black culture when one considers the experiences of ‘relocation’ and ‘displacement.’

When following the development of Gypsy Jazz throughout the 20th century, and in particular in the 1970s, it could be argued that it’s history and development is so influenced by American Jazz that it poses the question as to whether Gypsy Jazz can be considered as a totally separate genre in itself, or just as style under the Jazz ‘umbrella’. One element that remains constant is technique, repertoire and instrumentation, but it is debatable whether this is enough to label it as a genre in it’s own right. I have already argued that Gypsy Jazz in the 1970s ‘absorbed’ much influence from American Jazz music of the time, and that this was also true of Reinhardt and his contemporaries; as explained in the sleeve notes for the ‘Gypsy Jazz’ (2007) compilation album. (Author not credited):

“The Gypsies are an ancient nomadic people. Their origins lie in the Indian sub-continent. At some point in their ancient history the gypsies split into two main tribes, the Manouche and the Gitanes. Perhaps the biggest distinction between the Manouche and the Gitane is Geographical. The Manouche travelled through the Middle East, then, via the Balkans and Hungary, took a Northern sweep into Europe. The Gitanes came up through Southern Europe and Spain… The music of the Gypsies was influenced in rather the same way, as their music absorbed aspects of many other musics.”

This quote is controversial in that one could argue that much of the world’s population has its origins in the Indian sub-continent but it also implies that the music of the ‘gypsies’ was a consequence of their geographical relocation. The sleeve notes stress the assumed enigmatic nature of ‘gypsy’ lives and music that have their origins in ‘exotic’ locations – as the mysterious ‘other.’ However, whilst recognising outside influences, it does not consider American Jazz as a defining feature of the music, but takes a very much more partial view involving its ancient origins. I argue that Gypsy Jazz, rather than having specific and tangible elements, is a developing genre much in the same way that Gilroy uses the metaphor of the sailing ship in The Black Atlantic to describe the complex processes involved in creativity.

In The Black Atlantic, Paul Gilroy draws attention to the transnational and evolutionary character of black music and argues that it should, as Leitch describes, transcend “ethnicity and nationality to produce something new.” According to Leitch, “Gilroy deplores ethnic and nationalist absolutisms, and champions transnational hybridities, particularly their forgotten histories.” Leitch states that Gilroy effectively claims that fascism is an aspect of many peoples’ cultural experiences when differences between cultural groups and individuals are entrenched. Indeed, in an epigram to chapter three of The Black Atlantic Gilroy quotes Adorno:

“Since the mid-nineteenth century a country’s music has become a political ideology by stressing national characteristics, appearing as a representative of the nation, and everywhere confirming the national principle…Yet music, more than any other artistic medium, expresses the national principle’s antimonies as well.’

Adorno argues here that a static definition of a ‘national’ music is highly suspect since it reinforces negative ideas of imperial ‘nationhood’ evident in the mid-nineteenth century and evidence of concomitant xenophobia. In addition, Adorno asserts that music is the creative art that is most able to relay a more complex vision of nation and its contradictions. Gilroy asserts that all art, including music is ‘processual,’ meaning that musical style is not ‘fixed’ and defined at one point in history. In this sense, the crisis of modernity in the 1970s can be considered alongside a tradition that has been constructed and continually reinforced through the adherence to Reinhardt’s legacy. As Gilroy states, it is strange that:

“The contemporary debates over modernity and its possible eclipse…have largely ignored music. This is odd given that the modern differentiation of the true, the good, and the beautiful was conveyed directly in the transformation of public use of culture in general and the increased public importance of all kinds of music.”

As mentioned earlier, I consider that the correlations between American Jazz and Gypsy Jazz are as important as any correlation with Roma performance practices or ancient origins. Gilroy describes the ‘values’ of music as being associated with its origins, but as something more mutable: “particularly if they come into opposition against further mutations produced during its contingent loops and fractal trajectories? Where the music is thought to be emblematic and constitutive of racial difference rather than just associated with it, how is music used to specify general issues pertaining to the problem of racial authenticity and the consequent self-identity of the ethnic group?” I argue that Gilroy’s definition of ‘mutations’ can be applied to the developing interrelationship and shared history of American Jazz and Gypsy Jazz, and the similar ancient origins of both in the Indian sub-continent. These ‘contingent loops’ and ‘fractal trajectories’ describe evolutionary processes and are arguably what make Gypsy Jazz, and indeed any other category of music, a living genre rather than a static one and solely as a historical performance practice devoted to Reinhardt.

Ralph Ellison’s observation on Jazz, in relation to identity in particular, states that the notion of a static genre in music is contradictory since it necessarily requires creative freedom. Indeed, he writes that Jazz is an ‘individual assertion’ by means of improvisation and alteration of traditional material. In this case, “the Jazz man must lose his identity even as he finds it.” Gypsy Jazz was therefore clearly influenced by the musical stimuli of genres closely surrounding it, as well as an element of spontaneous creativity. Ellison writes:

“There is a crucial contradiction implicit in the art form itself. For true jazz is an art of individual assertion within and against the group. Each true Jazz moment… springs from a contest in which the artist challenges all the rest; each solo flight, or improvisation, represents (like the canvasses of a painter) a definition of his [sic] identity: as individual, as member of the collectivity and as a link in the chain of tradition.”

In Ellison’s opinion, it is in the nature of the genre of Jazz to encounter these ‘mutations’ and then evolve within the music. It is therefore possible to consider that the modernization of Boulou and Elios Ferre’s style as the product of a processual development of their own identities within Gypsy Jazz. In particular, Boulou Ferre’s involvement with Jazz Fusion in the 70s can be seen as the most radical development of an established performer of Gypsy Jazz.

In relation to Jazz music of the 1970s, the crisis in tradition was arguably evoked by commercial viability; hence the amalgamation of Rock music and the formulation of Jazz Fusion. As discussed in chapter two, similar attributes, including studio effects, found their place in the work of Boulou and Elios Ferre. To many critics, Jazz Fusion and musical ‘mutations’ were considered ‘cultural contamination’, rather than an enriching musical factor. As noted earlier, Gypsy Jazz, in its ‘classical’ form has predominantly been an acoustic practice, with amplification and technology used purely to resolve issues regarding balance technicalities rather than a defining feature of the music.

However, Cosmopolitanism is highly controversial and critics state that it ultimately results in a notion of a homogenous society and catastrophic loss of authentic culture. Academics and activists such as Nadi Edwards crticise Gilroy’s work for equating ‘black community’ with the ‘oppressed,’ arguing that Gilroy’s stance involves too large a generalization and, what is more, continues to negatively define black communities in relation to the prevailing hegemony (what Braidotti states as ‘A as not B’). Françoise Vergès criticises Gilroy’s work in, ‘Monsters and Revolutionaries: Colonial Family Romance and Métissage’ (1999), saying that the, “exclusive focus on the Atlantic slave trade hinders the explorations of other areas”.

However, Rosi Braidotti would argue that hybridity is an inevitable state. Gypsy Jazz has developed to a certain point musically, thus demonstrating these ‘contingent loops’ that are shifting and forever changing. It may be impossible to entirely define Gypsy Jazz by its musical aspects in a prescriptive way, because it must inevitably evolve. However, It seems that Django Reinhardt’s legacy has become reason enough for many to employ ‘Gypsy Jazz’ as a fitting label for their music. This prescriptive approach to musical creation is a limiting factor for artistic creativity, which could be seen to go against its evolutionary and processual nature.

Conclusion

Reinhardt’s primary source of influence was similar to American jazz music of the time. I argue that a similar correlate is true of guitarists of the 1970s.I have concluded that Gypsy Jazz guitar is a synonym for music in the style, or in some respect homage to Django Reinhardt. The genre firstly defines music that is created on the foundations of Reinhardt’s Legacy, but not as a sustainable genre in it’s own right. Gypsy jazz is not a genre so much as a style of musical performance. Performers in the 1970s have inherited this performance ‘gene’ in different ways, but taking the music in different directions.

Despite some musicians developing the music in different directions the notion of inheritance is reinforced by both traditionalists and innovators who claim allegiance to the work of Reinhardt. The innovators of the 1970s believe that they preserve some essence of Gypsy Jazz, even though they are predominantly following American jazz styles. It can be argued that much in the same way, composers of the Romantic era used Beethoven (1770-1827), as their source of compositional inspiration. Despite later composers also taking influence from, and claiming allegiance to, the ‘great composer’, the music evolved in very different directions. Therefore, authenticity and innovation need not be seen as mutually exclusive but as part of the complex process of evolution.

The work of Reinhardt and the Quintette du Hot Club de France is undoubtedly canonic, but the notion of a ‘canon’ itself is perhaps intrinsically problematic since it suggests elements of stasis and elitism. Inevitable crises occur in tradition but arguably, rather than challenging authenticity, this results in radical mutations that constitute a highly creative evolutionary process. When Gypsy Jazz was reinvented in the 1970s, although lacking certain elements of the classical style, the music was still largely inspired by Reinhardt’s legacy and consequently the idioms of the guitar. The reinvention of the 1970s was a necessary development in breaking away from potentially limiting historical stylistic boundaries. I have concluded that this was noticeable in the works in ‘Pour Django’ and ‘Gypsy Dreams’ by Boulou and Elios Ferre, and Boulou Ferre’s work with ‘Emergency’. Many other Gypsy Jazz musicians, including Django Reinhardt’s son, Babik Reinhardt, also practiced this ‘reinvention’.

One quote in particular, I feel encapsulates the link between music and conceptions of time, such as the reinvention of Gypsy Jazz in the 1970s. James Baldwin writes:

“Music is our witness, and our ally. The beat is the confession which recognizes, changes and conquers time. Then, history becomes a garment we can wear and share, and not a cloak in which to hide; and time becomes a friend.”

Gypsy Jazz is a case-in-point and supports this argument. It is a genre that has a processual and instinctual drive towards evolution whilst retaining its loyalty to the legacy that Django Reinhardt and the Quintette du Hot Club de France initiated.

Bibliography

(No credited Author): Accompanying Digital Booklet- Gypsy Jazz. Proper Records Ltd. 2007.

ANICK, Peter. ‘Bireli Lagrene: A Gypsy Virtuoso Returns to the Music of his Youth’. (2003). Fiddler Magazine. <http://www.wideospaces.com/peter/folk_routes/panick_bireli.htm>(date last accessed, 10/11/13).

ANTONIETTO, Alain. Liner notes from: Baro Ferre, Swing Valses. Produced by Charles Delauney. Re-edition by Jon Larsen. Hot Club Records, 1988.

AYEROFF, Stan. The Music of Django Reinhardt; Forty-four Classic Solos by the Legendary Guitarist with a Complete Analysis. Mel Bay Publications, 2002.

BALDWIN, James. ‘Of the Sorrow Songs: The Cross of Redemption’, Views on Black American Music, no.2. 1984-85. P.12.

BRAIDOTTI, Rosi. Metamorphoses: Towards a materialist theory of becoming. Cambridge, Polity Press, 2002.

CANNON, Steve and Hugh Dauncey. Popular Music in France from Chanson to Techno: Culture, Identity and Society. Ashgate popular and folk music series. Ashgate, 2003.

COOK, Richard and Brian Morton. ‘Miles Davis’. The Penguin Guide to Jazz. 8th ed. New York: Penguin, 2006.

CROFT, John. ‘Thesis on Liveness’. Organised sound 12. Cambridge. 2007.

CRUICKSHANK, Ian. The Guitar Style of Django Reinhardt and the Gypsies. Wise, 1989.

DAVIS, Ursula Broschke. Paris. Found in: Paul Gilroy. The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness. Verso, 1993. P.18.

DELAUNEY, Charles. Django Reinhardt. London: Cassell, 1961.

DEVINE, Kyle. Lecture 6 slides: ‘Technology Week 1: Capturing Sound’ Popular Music Studies. lecture notes. Lecture 6 given on 07/03/14 at City University.

DREGNI, Michael. (2004). Django: The life and music of a Gypsy legend. New York: Oxford University Press.

DREGNI, Michael. Gypsy Jazz: in search of Django Reinhardt and the soul of Gypsy Swing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

ELLISON, Ralph. Shadow and Act. New York: Random House, 1964.

FRITH, Simon. ‘Music and Identity’. Questions of Cultural Identity. Ed. Stuart Hall Paul du Gay. SAGE, 1996.

GILROY, Paul. The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness. Verso, 1993.

GLISSANT, Edouard. Translated from the novel: Malemort. Paris: Seuil. 1981. Quoted in: Paul Gilroy. The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness. Verso, 1993

HOOKER, Lynn. (2007). Controlling the Liminal Power of Performance: Hungarian Scholars and Romani Musicians in the Hungarian Folk Revival. Cambridge University Press.

JACKSON, Jeffrey H. (2003) Making Jazz French; Music and Modern Life in Interwar Paris. American Encounters/Global Interactions. Duke University Press, 2003.

LEITCH, Vincent et al. Eds. The Norton Anthology Of Theory and Criticism. W. W. Norton Company. London and New York. 2010.

MICHAEL, James et al. ‘Reinhardt (ii).’ The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, 2nd ed.. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, <http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.wam.city.ac.uk/subscriber/article/grove/music/J675400pg1.>(date last accessed April 28/4/14)

MOON, Tom. 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die: A Listener’s Life List. Workman Publishing, New York, 2008.

PETERS, Gary. The Philosophy of Improvisation. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

ROMANE, and Derek Sebastian. L’Esprit Manouche: A Comprehensive Study of Gypsy Jazz Guitar. Pacific, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications, 2004.

TYLER, James. ‘The Italian Mandolin and Mandola 1589-1800’. Early Music, Vol.9, No.4, Plucked-String Issue 2, pp. 438-446. Oxford University Press. (Oct, 1981).

VERNON, Paul. Jean ‘Django’ Reinhardt: A contextual bio-discography 1910-1953. England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2003.

WHITE, Bob W. Music and Globalization: Critical Encounters (Tracking Globalization). Indiana University Press, 2001.

WILSON, Andy. Faust – Stretch Out Time 1970 – 1975. Published by: Andy Wilson, 2006.

YUROCHKO, Bob. A Short History of Jazz. Rowman and Littlefield, 1993.

Websites

(No credited author). ‘Fesitval Django Reinhardt Samois s/Sienne’. (2013) <http://www.festivaldjangoreinhardt.com/spip.php?article957> (date last accessed, 12/11/13).

‘Boulou & Elios Ferre – Pour Django’. Discogs. <http://www.discogs.com/Boulou-Elios-Ferré-Pour-Django/release/2060571>(date last accessed, 22/03/14).

ETHERIDGE, John and Alyn Shipton. ‘Django Reinhardt’. BBC radio 3. Friday 28 December 2007, 22:30. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b008jf9w

GOTTLIEB, William. Portrait of Django Reinhardt, Aquarium, New York, N.Y, c.a. Nov. 1946. < http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/wghtml/wgpres11.html> (date last accessed, 01/05/14).

Patrus53. Babik and David Reinhardt & Django Painting. (2011) < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SvphEb1rEro>(date last accessed, 12/4/14).

Quintette Du Hot Club De France. Discogs. < http://www.discogs.com/artist/355185-Quintette-Du-Hot-Club-De-France>(date last accessed, 04/05/14)

SADAKA, Edmond. ‘Boulou Ferré’. Festival Django Reinhardt Samois s/Seine. (2012) < http://www.festivaldjangoreinhardt.com/spip.php?article917>(date last accessed, 06/05/14).

WEGEN, Michel. ‘Wegen’s Guitar Picks’ (no date given) Wegen Picks. <http://www.wegenpicks.com/#gypsy> (date last accessed, 12/11/13).

WINTHER, Nils. Boulou & Elios Ferre, ‘Gypsy Dreams’. 1980. Discogs. < http://www.discogs.com/Boulou-Elios-Ferré-Gypsy-Dreams/release/2661020>(date last accessed, 05/05/14).

Discography

BOSQUET, Etienne ‘Patotte’. ‘Les Yeux Noirs’. Gipsy Jazz School – Django’s Legacy. Iris Music – 3001 845. 2006.

CHRISTIAN, Charlie. ‘Dinah’. The Original Guitar Genius. [Disc 3]. Proper Records. PROPERBOX 98. 2005.

DEBARRE, Angelo, ‘Cherokee’, Gypsy Jazz School (Various Artists). Disc 2, Track. 11. France: Iris Music – 3001 845. 2006.

EMERGENCY. ‘Infidels’. Homage to Peace. America Records. 980 691 – 7. 2004.

FERRET, Baro. ‘Panique’, Gypsy Jazz School – Django’s Legacy. Iris Music – 3001845. 2010.

FERRE, Boulou and Elios. ‘Nuages’. Pour Django. SteepleChase – SCS-1120. 1979.

FERRE, Boulou and Elios. ‘Panique’. Gypsy Dreams. SteepleChase – SCS 1140. 1980.

FERRE, Boulou and Elios. ‘Rhythm Futur’. Pour Django. SteepleChase – SCS-1120. 1979.

LA FUENTE, Feat. Rosenberg Trio. ‘Guitarra (Radio Edit)’. Guitarra. Soundz Good Recordings – SGR 100165. 2010.

MORTON, Jelly Roll. ‘Mushmouth Shuffle’. 99 Hits: Jelly Roll Morton. 99 Music. 2009.

MORTON, Jelly Roll. ‘Kansas City Stomps’. 99 Hits: Jelly Roll Morton. 99 Music. 2009.

PASS, Joe. ‘Cherokee’, Virtuoso. A6. Pablo Records – 2310 708. 1974.

REINHARDT, Django, ‘Anouman’, Keep Cool (Guitar Solos 1950-53). FiveFour – FIVEFOUR 14, 2006.

REINHARDT, Django. ‘Improvisation’. The Ultimate Collection. Stardust Records. 2008.

REINHARDT, Django. ‘Les Yeux Noirs’, The Best of Django Reinhardt. Blue Note – 724383713820. 1996.

REINHARDT, Django. ‘Minor Swing’, The Ultimate Collection. Stardust Records. 2008.

REINHARDT, Django. ‘Nuages’, The Ultimate Collection. Stardust Records. 2008.

REINHARDT, Django. ‘Rhytme Futur’. The Ultimate Collection. Stardust Records. 2008.

REINHARDT, Django. ‘When Day is Done’. The Ultimate Collection. Stardust Records. 2008.

REINHARDT, Django and Stephane Grappelli. ‘Dinah’, Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli with the Quintette of the Hot Club of France: The Ultimate Collection [Disc 2]’. Track 12. Not Now Music – NOT2CD251. 2008.

Interviews

Robin Nolan (17/01/14)

There are few people who can play it at such a high level. Do you think you have to be born a Gypsy to do it?

No. Not anymore. Players like Andreas Oberg, Olli Soikeli and many others have proved that you don’t have to be a Gypsy to play to a high level. Gypsies learn this music from a very young age and often don’t go to school so dedicate their whole childhood to mastering this music. Now with the Internet everyone has access to see how the gypsy players are playing and dedicate themselves. Saying that I can usually tell by listening if the player is a gypsy or not – this has to do with the feel which not being a technique is harder to learn. Still some mystery there!

Are there any constraints performing this style as a non-Gypsy?

No constraints for me personally but again living in a gypsy community would be very conducive to playing this style with the support etc – music is very important to them so encouragement and inspiration is a plenty.

What do you feel are fundamental techniques to the style?

Do you feel they are universal amongst players?

The right hand technique is the most important in defining this music from others and is vital in becoming accepted as a gypsy jazz player. The rhythm is the other defining technique, which absolutely defines this music. It replaces the drums and gives it that recognisable swing not seen in other music. The harmony is always evolving like with jazz but the rhythm defines.

There is a big focus on tradition, and traditional values in the music. What do you think of the ‘importance of tradition’ in Gypsy Jazz music?

Tradition is a great place to start but you must always remember that Django was an innovator and was constantly looking for new ideas and music. He was ahead of his time. I’m not so into preserving the tradition but many are. The guitars and paraphernalia (picks, strings etc.) are a fun part of this style (like heavy metal) and the guitars and the luthiers are very important.

Jonny Hepbir (13/01/14)

There are few people who can play it at such a high level. Do you think you have to be born a Gypsy to do it?

No, I think that the Jazz-Manouche style is fully accessible to every type of player (guitarists). With the increase/saturation of Internet material available these days it’s easy to progress to a reasonable standard. There are more and more musicians picking up on it, not just guitarists. It’s also a good ‘in-road’ to the jazz vocabulary for players who might have been daunted by the myriad academic approaches to jazz. Everything is nicely set out.

Are there any constraints performing this style as a non-Gypsy?

Based on my own experience from playing at length with some of the foremost Roma guitarists in the style, I would say the only true dividing line is the cultural one. There are literally only a small handful of non-gypsy players in the world who can communicate the authentic feel that the Roma have with the guitar and its role in gypsy jazz. The reason for this, I believe, is due to their integration at young ages with Roma families, learning from the older relatives as though they were part of the family.

Technical fluidity both in rhythm and solo abilities, plus creative harmonic invention are equal these days amongst the top Roma and non-gypsy players. It’s the feel/accent that is subtly different. Not wrong, just, different. I could easily draw up a list of comparisons with the aid of YouTube. It’s also the reason why Django Reinhardt could take on the world’s top ‘Jazzers’ back in the day and keep people enthralled and baffled throughout his life, up to the present and without a doubt, far into the future.

What do you feel are fundamental techniques to the style?

Do you feel they are universal amongst players?

The fundamental techniques (for a guitarist) are rhythm and melody/solo. Very demanding on all levels. Relaxation with strength, especially for the plectrum arm. Very difficult to achieve if you want to sound like a gypsy player. I think these are universally recognised if you want to set out on this path, but the understanding/opinion of how the two work together is as varied as the amount of people playing it these days. Personally, I take all my technical lessons from Django and the Roma. For gypsy jazz, they tick all the boxes for me. Harmonically, everyone/everything is open season. There are so many brilliant musical approaches now on the International gypsy jazz scene propelling the genre into tomorrow and attracting new fans.

In regard to rhythm, La pompe is a much-debated subject. What do you feel is necessary for good rhythm playing?

Timing and feel. You have to be solid and strong yet light and bouncy! A good rhythm player will have the perfect vehicle to become good soloist if he or she chooses. With some non-gypsy players you sometimes can get great soloing which becomes slightly tainted when you hear them take over rhythm. Maybe not necessarily a timing issue, more of an accent/bounce thing. All those great Roma soloists are all excellent rhythm players. They did that first; it showed them how to do it.

What aspects do you feel are most important in defining the style as ‘Gypsy Jazz’, is it rhythm, melody, technique?

Personally, it’s rhythm. For me there lays the feel, accent and bounce. Technique can be learnt through practice. Taking the rhythm and hopefully putting that to the melody/solo. Then trying to be as musical as possible.

There is a big focus on tradition, and traditional values in the music. For example, Selmer style guitars, Django as a common denominator. What do you think of the importance of tradition in Gypsy Jazz?

With gypsies, tradition is important, with non-gypsies, I don’t think it plays a huge part (musically) anymore. Everyone loves a Selmer guitar; they look awesome and sound cool. Musically, these days, it’s very hip to throw in ideas from any part of the jazz/harmonic spectrum. As I mentioned before, it keeps things fresh, progressive and encourages new blood onto the scene. It’s very difficult to get your own ‘voice’ in the style because of the general high standard, but I think that it’s the only way forward if you want to get noticed.

Denis Chang (27/01/14)

There are few people who can play it at such a high level. Do you think you have to be born a Gypsy to do it? Are there any constraints performing this style as a non-Gypsy?

This is a difficult question to answer and it especially depends on how one defines Gypsy Jazz. It also depends on how you would define ‘high level’. For starters, even within Gypsy communities, some are musically described as not being Gypsy enough, or too Gypsy. In France, I was told by Gypsies to never emulate certain Gypsies from Holland, because they were too academic and not ‘Gypsy’ enough. In Holland, I was told by Gypsies that certain players in France sounded too Gypsy and sloppy. So you see how complicated it gets; I would rather not name names. Then in Paris, France, since about 15 years, a scene has been growing in which non-Gypsy players have been learning to play the style and turning it into something a bit more sophisticated.