DjangoBooks.com

Welcome to our Community!

Categories

- 20K All Categories

- 1.1K General

- 485 Welcome

- 60 Archtop Eddy's Corner

- 147 CD, DVD, and Concert Reviews

- 385 FAQ

- 26 Gypsy Jazz Italia

- 27 Photos

- 209 Gypsy Picking

- 21 Unaccompanied Django

- 15 Pearl Django Play-Along Vol.1

- 17 Gypsy Fire

- 45 Gypsy Rhythm

- 1.4K Gypsy Jazz University - Get Educated

- 131 Gypsy Jazz 101

- 231 Repertoire

- 228 History

- 709 Technique

- 51 Licks and Patterns

- 6 Daniel Givone Manouche Guitare Method Users Group

- 20 Eddie Lang Club

- 1.3K Gypsy Jazz Gear

- 816 Guitars, Strings, Picks, Amps, Pickups and Other Accessories

- 465 Classifieds

- 52 Recording

- 64 Other Instruments

- 18 Violin

- 5 Mandolin

- 23 Accordion

- 7 Bass

- 11 Woodwinds

- 352 Gypsy Jazz Events

- 145 North America

- 112 Europe

- 95 International

In this Discussion

Who's Online (0)

Mario Maccaferri's design inspiration

BillDaCostaWilliams

Barreiro, Portugal✭✭✭ Huttl, 9 mandolins

BillDaCostaWilliams

Barreiro, Portugal✭✭✭ Huttl, 9 mandolins

I had always assumed that Maccaferri, being a classical guitarist, was mainly influenced by classical guitar design but two recent studies suggest that he was inspired by the knowledge he picked up about mandolin design when he served as apprentice to luthier Luigi Mozzani in Italy.

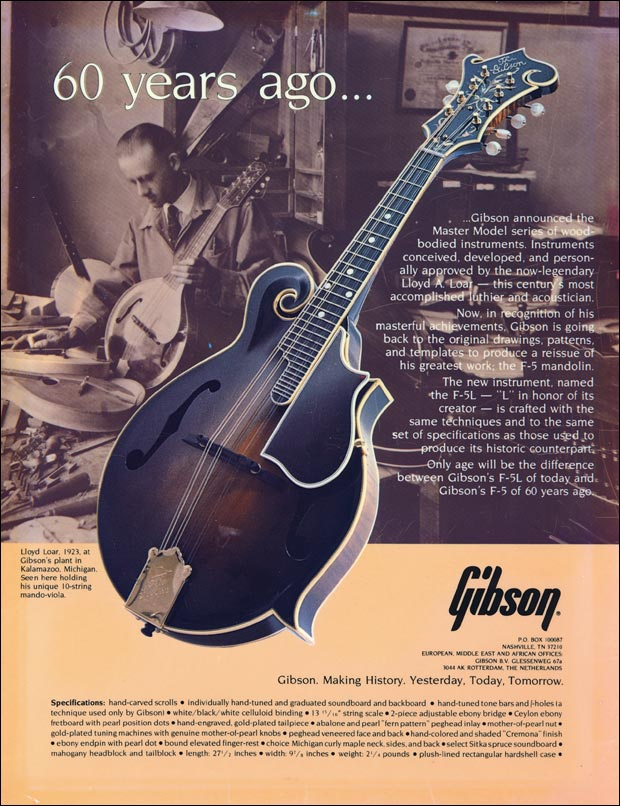

He may also have been influenced by Gibson’s F5 mandolin launched in 1922.

Emberger Neapolitan mandolin

Gibson F5

In a 2016 conference paper Russell Spiegel of the University of Miami writes:

*********************************

“At his Paris workshop, Maccaferri began by organizing the tools and machinery

and started training the workforce. All the moulds, templates and special tools were

designed by Maccaferri and made on site. It was then that his revolutionary design began

to take form. At Henri Selmer’s request, Maccaferri had been asked to make designs for a

number of different models – classical, concert harp (with between two and six extra

resonating strings), Hawaiian, and, due to the aforesaid popularity of jazz bands, a steel-

string “jazz” model, known as the ”Orchestre,” of which this paper is concerned with,

along with a four-string version.

The first guitars began production in 1932 with Maccaferri concentrating first on

classical models. To learn more about jazz he began frequenting the Paris clubs and got

to know what guitarists there were looking for. Though virtually all the instruments

Maccaferri constructed for Selmer entailed design improvements, for him the most

important features were incorporated into the Orchestre model, which introduced a

number of improvements that were to influence guitar makers worldwide.

One look at this instrument and one immediately recognizes they are looking at an

instrument quite different from the guitar of Torres. Inspired by Neapolitan mandolins

Maccaferri’s guitar incorporated a vast series of innovations which will be shortly noted

here:

The Body: The majority of the backs & sides were made of 3-ply laminated Indian

rosewood. Some used laminated Brazilian rosewood or mahogany, and a few used

solid birdseye North American Maple. At the time laminated wood was an

innovation – Maccaferri noticed that solid wood bodies tended to damage more

quickly and laminated woods tended to be stronger and last longer, as well as

making the body lighter. Inspired by the F-style mandolin the instrument also

incorporated a distinctive cutaway to allow better access to the higher frets

The Top: Always made of 2 halves joined at the middle of European spruce, the

tops of the Orchestre were curved without being archtops.

The Neck: The vast majority of necks were 3-piece European walnut lined with

three or four 2x12mm duralumin plates, lightened with holes bored in them.

Though non-adjustable, they added to the stability of the neck. The fingerboard

was made of ebony and also boasted a zero fret on the basis that it improved

intonation. On D-holed instruments the fretboard continued allowing 24 frets on

the 1st string only. Oval holed models stopped short of the soundhole.

Tailpiece: Maccaferri again used mandolin design to come up with a unique

tailpiece that affixed to the bottom of the body.

Bridge: Here Maccaferri used the mandolin principle of having a floating bridge as

opposed to a bridge glued to the body. These guitars came with a number (usually

seven!) of bridges with different heights to accommodate the needs of any player.

Another very characteristic element in the design of this guitar were the

“moustaches” on the sides of the bridge. The use of these “moustaches” were not

merely ornamental as they served as guides to align the bridges correctly.

Tuning Machines: These represented an entirely new design patented by

Maccaferri that enclosed the gears inside a casing fixed to a base plate. This casing

protected two cog wheels ensuring permanent self lubrication of the gears, which

was not possible with open tuning machines. It also increased the number of teeth

and improved the tooth angle so that at least four teeth were in permanent contact

at any time leading to greater sturdiness, precision, and less wear.

The Soundbox: Another distinctive characteristic of the Selmer Maccaferri is the

the big D, or “grand bouche” soundhole. In part created for a bigger sound, but

also to compensate for the guitarist leaning over his instrument thus muffling part

of its tone, and inspired by 19th century romantic guitars and harp guitars he had

learned to construct in Mozzani’s shop, Maccaferri improved on the design to add

volume, tone, and clarity to the guitar, receiving a patent in 1930. Basically a box

within the body, the resonator had a reflector that enabled the sound to be directed

out of the soundhole. The D soundhole’s function was thus purely pragmatic as

Maccaferri found that with a smaller soundhole he was not able to achieve the

desired results.

Overall, around 200 guitars were produced in the first year with almost all being

sent to London. In 1933, while Maccaferri went back to concert touring the factory turned

out fewer guitars, the majority being 4-string models. Around this time, however,

Maccaferri had a falling out with Henri Selmer (the actual details are unclear, but it had

evidently to do with the limited duration of his contract) and left the company with the

oversight of construction of the guitars falling to Maccaferri’s deputy Lucien Guerinet."

*********************************

A similar argument is made on page 63 of the 2025 doctoral thesis by Brazilian guitarist Leon Bucaretchi.

Leon has been a regular at jams here in Lisbon while working on his study.

The thesis is in Portuguese but the abstract is in English:

"In this research, we studied the vibratory characteristics of the Manouche guitar in the laboratory and detailed its morphology, referencing discussions with luthiers specialized in this instrument’s construction. Two years of fieldwork allowed us to view this instrument inserted into context, observing how it is used, by whom, and the importance of community practice and the pedagogy of jazz Manouche in the sound we hear when a musician plays a Manouche guitar.

Therefore, this thesis elucidates how the characteristics of an instrument, sound conceptions of musicians of the Manouche genre, and performance techniques interconnect to define the sound of the Manouche guitar."

Comments

“These guitars came with a number (usually seven!) of bridges with different heights to accommodate the needs of any player”

7! First time I have heard this.

thanks for posting...

I'm no expert but I'm pretty sure the pliage in these guitars also derive from the Neapolitan mandolin -- at least for their makers -- but its weird the author would omit mentioning such an important feature. Maccaferri's 1932 Orchestra model had a canted (not arch) top! I also didn't know about the tuning machines he patented, or the 7 bridges.

I think we're due a good researched study on the genealogy of the SelMac. I'd love to know more about the role of the Busatos, the Geromes, Burgassi, etc. -- not just Maccaferri. Yeah there were innovations but lots of stuff, I imagine, was probably also adapted & developed from pre-existing ideas, and from other luthiers at the time. I doubt they all simply copied Maccaferri. Granted, he seems to be a fascinating character -- artist, innovator, entrepreneur, and not lacking a sense of humor either. Those plastic guitars -- ingenious and hilarious at the same time. (BTW, Marco La Manna & several other luthiers, I understand, are actually working on designing a paper maché guitar! Ah... I can hear you laughing. But who knows? Maybe they'll work somehow.)

His plastic guitars didn't take off the way he wanted it to but plastic ukes were a huge hit, they sold them by millions.

I could see buying myself either one - just not without trying it in person.

Maccaferri's own words:

… after the production of the first guitars, Selmer

asked me to make three new models, a Spanish style

classical guitar, an Hawaiian guitar and a jazz guitar.

For the first two there were no problems, but having

not a jazz background I started to do researches on

the subject attending jazz clubs and I realized that

a specifically made guitar should have a loud and

piercing sound.

To obtain that effect I designed a guitar with a con-

vex soundboard (like a mandolin).

I used a non fixed (floating) bridge and a string plate

similar to the ones used on mandolins.

I’m glad to say that the guitar was really successful,

and the popularity of the instrument was increased

by Django Reinhardt. Even if we never met, our

names are inextricably tied together. (…)

Antonio Torres made the first paper mache guitar (back and sides) in 1862 to prove his theories about the relative unimportance of the wood for those parts. The guitar still exists in a museum in Barcelona, though it's in bad shape, I've read. Luthiers fall into that class of craftsmen that I would call tinkerers, who make functional objects and will immediately appropriate any ideas that they think will improve on their own ideas. And they are always thinking and dreaming up new ideas. The guitar world has been blessed with many of these tinkerers - Torres, Orville Gibson, Michael Kasha, Mario Maccaferri, the Larson Bros, Lloyd Loar, and so many others - like Paul McEvoy... A lot of things that make our lives better were thought up and developed by tinkerers. One example: variable speed windshield wipers.

I wish I could recommend a single reference book on this subject of guitar evolution, but I don't think there is one. A good one for now is "Guitars from Renaissance to Rock" by Tom and MaryAnn Evans. It was published in 1982 but is still useful as there haven't been a whole lot of new developments since then.

I think Maccaferri was like Orville Gibson, a real original.

All the builders I've encountered (and many of the repair tech/restorers) have a big tinkerer streak, expressed as much in devising and making tools and jigs as in fiddling with instrument design. When I interviewed Jim Olson, we spent almost as much time talking about his shop tools as his guitars. And one of my fondest memories of a late friend who repaired just about every guitar in town: he'd look at a job, literally stroke his chin, and say, "I wonder if a fella could. . . " before trying out some idea.

One of my favorite guitars--I've been playing it for more than 30 years now--is the result of its builder messing with design elements and innovations to produce the kind of guitar *he* wanted to play. (He was also a fine composer and performer.) The crucial sonic elements were probably his bracing pattern, half X/half fan (requiring very light strings), combined with a redwood top and a 12-fret neck (other elements were for playability). Here's a video of him playing his personal guitar, a late build which is a bit different from mine--a body inspired by the Santa Cruz F. (Mine looks like a small dreadnaught and is an inch smaller at the lower bout.)

Is that cutaway upper bout tough to bend? It looks like the side there goes through ~165 degrees or more in a small space. It looks even more acute than a typical venetian cutaway.

I'm one of those who built guitars based on what I wanted to hear when I played (when I wanted something not exactly like a gypsy jazz guitar). The result was X-bracing, floating bridge/tailpiece, multiple side sound holes, domed bent top.

Must be...the Selmer cutaway is a bitch to bend for me and like 75% of things I've wanted to improve on my guitars have something to do with not getting the cutaway bent right. That archtop looks worse and archtops in general are terrible in that regard.

I have retooled my efforts and the last bend I did was the best. Partially using a Ken Parker technique of epoxying fabric (in his case linen) on the outside of the bend areas to keep the fibers intact and keep the crushing on the inside. I was too lazy to use linen though and then I heard Linda Manzer uses peel ply, which is a fabric you can lay into epoxy and it will leave a nice surface but then peel off. I was dubious whether it would work but it worked awesome.

22 guitars in, side bending still is a pain in the ass for me but I think I have it on the run to some degree.